In the early period of Canadian history, Samuel de Champlain founded Port Royal –the first permanent settlement in New France– in Nova Scotia (Acadia) in 1605. In 1606, Champlain founded a “gourmet club” called The Order of Good Cheer. It was probably the first organization of its kind, intended to raise the spirits of the group. In this group, each person was responsible for creating dinners for the other members and they tried hard to outdo one another. Unfortunately for us, they did not write down their recipes. Some time ago CBC Radio attempted to recreate dishes that potentially could have been served at these dinners. Not apparent in these recipes were the simple dishes that I associate with regional Canadian cuisine. It is my endeavor to verify the origins of the famous tourtiéres in New France, a ubiquitous dish analogous with regional Canadian cuisine.

It was shortly after Champlain’s time, that my matrilineal family came from La Rochelle, France to New Foundland. My grandfather Joseph Arsenault (Arcenaux, Arceneault) (a ship’s captain) and his brother Pierre came to Acadia in the mid 1700’s. My uncle went on to the Parish of Louisiana and my grandfather’s descendants then traveled through the east coast, into Michigan and back into Canada in the early 19th C. My roots as a French-Canadian reach back as well, to include my family who are Metis-Indian from Walpole Island and Pointe-Aux-Roches Ontario Canada, a Francophone community up until the first half of the 1900’s. My grandmothers’ cooking was famous, and I studied at her knee for a large part of my childhood. Tourtiére was a dish commonly served in our home, sometimes being comprised of pork, beef (or a combination thereof) bacon or –when available– venison. Regional Canadian cooking was not something I was aware of, only that I cooked how I was taught. These recipes were handed down generation to generation. My pie dough recipe for example, is at least 150 years old, having been given to me in 2001 by a pie maker who at the time was at the age of 82. In turn, the recipe was handed down to her while she was in her early 20’s by her 90-year-old great aunt, who received it from her own grandmother. This recipe is included below.

The food served at Port Royal in the early 1600’s is not going to be rendered exactly in the recipes I was handed down. They are based on recipes and cooking techniques that would have been brought with the explorer, rooted in the cuisines of medieval France. The ingredients and the execution of those recipes however, were most likely not completely familiar to the medieval cook. Having to rely on whatever was available in New France in the dead of winter, there would have been little option but to create recipes that used substitutions.

Over centuries, the recipe for the classic traditional pork pie, tourtiéres , evolved. Its roots can be found in the recipes of Taillevant (1300’s-1400’s), Master Chiquart (mid 1500’s) and later Francois Pierre La Varenne (mid 1600’s) and I’ll share those in the follow paragraphs. As with all recorded haute cuisine the first recipes are food created for nobles and the gentry who accompanied them in dining. These recipes generally reflected expensive ingredients, often ostentatious in their use in order to exemplify the grandeur of the table guests. Unlike the regional cuisine of the commoners, these dishes were often made with labor intensive and complicated methods requiring the hands of skilled cooks and plenty of unskilled kitchen workers. And unlike the cuisine of the nobles, these common recipes were rarely written down for posterity’s sake leading us to the application of cultural anthropology to get a better look at these undocumented recipes.

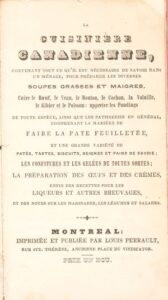

The first known Canadian cookbook was “La cuisinière Canadienne, contenant tout ce qu’il est nécessaire de savoir dans un ménage, pour préparer les diverses…. Montréal: L. Perrault, 1840”

found here http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/cuisine/002001-100.01-e.php

Although much later than our period of Early New France, this cookbook is written in French recipes in an early style, unredacted (primarily with no quantities or extended and defined directions). This approach to recipes was not changed until the development in the late 1800’s by Fannie Merritt Farmer in “The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book” 1896.

From what I can deduce, this mid 19th C. Canadian cookbook is the first to describe a recipe for what we could now say is the traditional Canadian Tourtiéres , a ground pork meat pie, seasoned with spices and herbs, baked in a crust.

Before we accept this recipe as a tourtiéres, however, we should examine its earlier predecessors that show a development from medieval style recipes of complicated form and ingredients, through to a simplification and refinement in the revolutionary 18th C. whose recipes differ from the 19th C rendition.

The Medieval Influence

Following is a brief analysis of recipes from the most significant cookbooks printed before the period of Samuel de Champlain’s exploration of Canada as well as continually reprinted for centuries after their first publication;

Please note that any comments or explanations I add will be in parenthesis.

Medieval Recipes for Pork Pies;

The following two recipes are probably one and the same, one an earlier version of the other. Note the basic and main ingredients ground mutton, veal or pork, bacon (plus additional herbs, spices, fruit, nuts, poultry as is common in medieval cuisine) baked in a crust.

Original Recipe: French Master Chef to King Charles the V and VI, Taillevent (Guillaume Tirel) 14th Century France[i]

This recipe is very ostentatious with gold leaf and flags and crenellated pastry to look like castle walls. But the fundamental ingredients and style is very much in the spirt of our elusive pork pie. Minced meat, with seasonings, and in this case fruit and nuts.

- Tourtes parmeriennes: Parmesan Pies. Take mutton, veal or pork and chop it up sufficiently small; then boil poultry and quarter it — and the other meat must be cooked before being chopped up: then get fine powder and sprinkle it on the meat very sensibly, and fry your meat in bacon grease. Then get large open pastry shells — which should have higher sides than usual and should be the size of small plates — and shape them with crenellations; they should be of a strong dough in order to hold the meat. If you wish, you can mix pine nut paste and currants among the meat, with granulated sugar on top; into each pastry put three or four chicken quarters in which to plant the banners of France and of the lords who will be present, and glaze them with moistened saffron to give them a better appearance. For anyone who does not want to go to such expense for poultry, all he has to do is make flat pieces of pork or of mutton, either roasted or boiled. When the pies are filled with their meat, the meat on top should be glazed with a little beaten egg, both yolks and whites, so that this meat will hold together solidly enough to set the banners in it. And you should have gold-leaf or tin-leaf to glaze the pies before setting the banners in them.

Here is another French pork pie, this time from the 15th Century. Much more detailed and complicated and layered with other game, poultry, fruit, nuts, herbs and spices this time with cheese added.

Parma Tarts- Master Chiquart- 15th C (1420’s) [ii]

This recipe although extremely long, is an interesting read. Prepared for a huge feast, the proportions are gargantuan but the technique intricate.

- Again, parma tarts: for the said parma tarts which are ordered to be made, to give you understanding, take three or four large pigs and, if the feast should be larger than I think, let one take more, and from these pigs remove the heads and the hams, and put the fat apart to be melted; and take the said pigs and cut them into fair slices or pieces and wash them very well and put them to cook in fair and clean cauldrons, and put in salt in measure. And for the said parma tarts you will need three hundred pigeons, two hundred very young chickens — and if it happens that the feast is given at a time when there are no very young chickens, have one hundred young capons — six hundred small birds; and these pigeons, poultry, and small birds should be plucked and cleaned properly and cleanly; and take the pigeons and split them in half, and also split the poultry and cut it in quarters; and then take the pigeons, poultry, and small birds and put into fair small casks, wash properly and cleanly three or four times in fair and clean water, and then put them to boil in fair and clean cauldrons, and put in salt in measure; and check that it does not cook too much; and, being cooked subtly, draw out your meat into fair and clean cornues and put your small birds in one place and the other meat in another. And then take your pork fat and cut a great deal of it and put into fair and clean pans and melt well and, being well melted, strain it into other fair and clean pans; and then take your small birds and sauté them in your lard lightly and not too much, and also next the other meat. And of figs six pounds and six pounds of dates, of pine nuts six pounds, of prunes six pounds, of raisins eight pounds; and then take your figs, prunes, and dates and cut them fine — as small as the smallest raisins — and remove the stems from the raisins and clean them well. And then take your pine nuts and rub them very well, then winnow them on fair platters; then put them on a fair cloth and pick them over and clean them well and properly so that there remains nothing but the white nutmeat. And then put your figs, prunes, raisins, dates, and pine nuts into a fair, white and clean cornue, and let it be well covered with a fair, white and clean cloth so that nothing which is not clean falls therein. And then arrange that you have herbs, that is sage, parsley, hyssop and marjoram, of which have such a large amount of parsely that you have a great bowlfull drained and with the leaves stripped off the stems, and sage, hyssop, and marjoram added in measure; then put them in a fair and clean cornue, and wash them well and properly in three or four changes of fresh water, and then put them on fair and clean boards and chop them very small. And check to see if your pork is cooked and put it on fair tables, and you should have your fair, large and very flat boards; and you who are making this fair parma tart, together with the assistants which you have assigned to it, take care to remove the skin of the said pigs and let no bones remain, and chop your meat very small; and in chopping your said meat take herbs and put them in with your meat; and then have a large, fair, clean and clear basin [bacine] and put your said meat therein — and to give understanding of what the basin is, I mean that this should be a fair and large pan of those in which one cooks big and large fish. And then arrange that you have a quintal of best Crampone or Brie cheese or the best cheese which can be found, and then take the said cheese and pare and clean it well and properly, and cut it small, then bray it in a mortar very well and strongly; then take six hundred eggs and moisten your cheese therewith in braying, and continually sprinkle with the said eggs so that they are well bound and moistened and according to the quantity of the parma tarts which you are ordered to make. And take the pan which I described to you above, and put therein lard which is refined in which one has sautéed the meat, and put it in according to the quantity of the stuff which you have, and let it be put over a fair clear fire; and have two good strong assistants stirring the filling strongly and firmly with a great slotted spoon with two hands, and then let it down over a fair fire of clear coals; and let your figs, prunes, dates, raisins, pine nuts, cut as is said above, be washed two or three times in fair, clean and clear water and then afterward washed in good white wine and then put to drain and dry on fair and clean boards; and then, being drained, throw it into your filling, and let it be very well stirred in; and then take your cheese which has been brayed and moistened with egg as is said above — the quantity which you have made for the said filling — and put into your filling while braying well and strongly; and take the said pan off the fire. And take your spices, white ginger, fine powder, grains of paradise, saffron to give color, and put in cloves in measure, put them therein and stir continually; and have a great deal of sugar beaten into powder and throw in a great deal according to the quantity of the filling, and stir continually. And arrange that you have fair and clean pans, or if you find fair and clean ceramic dishes take as many as you need to make your parma tarts in such great quantity that you will have some left over; and then when you have your fair and clean pans or ceramic dishes arrange that you have two or three thousand sugared wafers, and then take your pans or your ceramic dishes and take some of the lard in which you fried your small birds and poultry and put into your pans or ceramic dishes and then take your wafers and put in each dish on the bottom and around it a layer of the said wafers so that there are four or five one on another; and on the said wafers take of the said filling and make a layer, and then on top of the filling put the small birds here and there and not together; and put between two small birds a quarter of a pigeon and elsewhere a quarter chicken between two small birds, and do this in such manner that of small birds, quarter pigeons and quarter chickens there is made well and adroitly a layer set on top of the layer of the filling; and on top of this layer made of small birds, quarter pigeons, and quarter chickens is made another layer of the said filling, and on top of this layer made of filling put wafers in the fashion and manner which is said above as they were put on the bottom of the said pan or ceramic dish; and, this being done, they should be covered well and properly with the said wafers. Then take cold lard and put on top, and then put your tarts in the oven which has been well heated; and you will be well advised when they cook to have leaves of spinach and white chard well cleaned and washed so that, if the said wafers burn at all, you can put them on top. And then draw out your parma tarts and scrape them well and properly so that there remains nothing burned, and then put them on fair serving dishes; and, with them on the serving dishes, take your gold leaf and put it on your parma tarts in the manner of a chessboard, and powdered sugar on top. And when one serves it, let on each tart be put a little banner with the arms of each lord who is served these parma tarts.

Le Cuisinier Francais, 1653 translation of 1651 edition, Pierre Francois La Varenne-Introduced by Philip and Mary Hyman[iii]

In this later corpus of recipes, we find that the pastry section does not mention pork but does mention veal, venison, lamb, mutton and most significantly boar and a gammon of bacon. Most fillings for pies are large joints of meat or birds, veal and assorted fruit or seafood fillings. Pasties or hand held meat pies were made only of ham, mutton, venison and wild boar. Pork in and of itself was used in recipes roasted, stuffed, with a sauce, boiled or salted. Tourtes appear to be a variety of minced meats, combined with other items such as sweetbreads, mushrooms, cardoons. Sometimes these tourtes were combined with spices, sugar and herbs.

The types of pastry were either a simple flour, hot water crust a short crust (with lard or butter) or a puff pastry (choux pastry). The hardiest of these being the hot water crust with butter.

The recipes from La Cuisinière Canadienne, 1840[iv]

Here we get to the meat of the matter. The recipes I was taught to make. These recipes were translated by me, forgive me for any errors.

Des Pâtés du Tourtiéres

Il n’ya a que ceux au porc frais, qui se cuisent avec de la pâte au fond du plat, dans tour les autres, on n’en met générlament qu’environ une bordure du quatre doigts, tout aurtour du plat; puis on y place la viande avec parti du jus, jusqu’á la bordure il faut employer un plat creux, et on suivra des reste le directions ci-dessous

Translation

It has only those with the fresh pig, which are cooked with paste at the bottom of the dish, in turn the others, one does not put of it generally (other types of meat?), that approximately the edge of the (pie dough is) four fingers, all around the dish(an overhang); then one places there the meat with part of the juice, until the edge, it is necessary to employ a hollow dish, and one will follow the rest of the directions below

Au Muton

Faites revenir vos morceaux de muton ton dan le poële avec saindoux, les ayant poudrés de farine, avec poire, sel et tête de clous*, quands ils seront rôtis, ajoutez parsil, thym, marjolaine, avec une dimiarre d’eau; si vous trouvez que c’est assaisonné, fait les tout bouillir un moment, et jettez le dans un plat creux garni de quatre doigts de pâte autour; courvrez de pâte, laissant une overture au milieu, pour on bouquet de pâte, que vous leverez avec soin, quand le pâte sera cuit pour jetter un peu de jus que vous arez conserve, ce qui empêchera votre pâté d’être sec.

In Mutton

Return your pieces of mutton to your stove with lard, having powdered them with flour, with pepper, salt and cloves, when they will be roasted, add parsley, thyme, marjoram, one starts with water; if you find that it is seasoned, makes the whole boil one moment, and put it in a hollow dish furnished with four fingers of paste around; will cover of paste, leaving a overture to the medium (an edge), for one bouquet of paste, which you will raise carefully, when the paste is cooked(indicating hot water pastry?) for put a little juice which you will preserve, which will prevent your pie from being dry

*Tête de clous- Old French clou de girofle, literally: nail of clove, …

Meaning “stud”

- Culinarily, “stud” means to insert flavor-enhancing or decorative edible items (such as whole cloves, slivered almonds or garlic slivers) partway into the surface of a food so that they protrude slightly. For example, hams are often studded with cloves.

The Pastry Recipe

The pastry recipes in the earliest Canadian recipe book offered something I wasn’t expecting- namely a recipe for a pastry we called “Potés”. My Mémé taught me to make potés without a recipe, it was simply made with left over pastry dough and filled with whatever jams, jellies or fruit compotes we had available, brushed with egg or milk and dusted with sugar and baked. It was not until I read this recipe that I realized her “Potés” referred to the compotes mentioned below.

Des Tartes

Étendez la pâte mince dans le fonds d’une assiette, et placez y telles confitures que vous voudrez, vous mettez une bordure de pâte et faites cuire. On peut couvrir de Pâte, les tartes aux compotes.

Tarts

Extend the thin paste in the bottom of a plate, and place there such jams that you will want, you put a edge of paste and make cook. One can cover Paste, tarts with compotes.

Here we have many pastry recipes made after the way of these individuals.

Façon de P. Marcelais

Prenez une livre de beurre bien battu et sans eau, broyez le dans une livre et demie de farine, ajoutez y une chopine d’eau glacée, une pincée de sel, si votre beurre n’est pas trop sale; étendez cela mince, faites en un rouleau, remenant les deux estremités ensemble, battez la pâte, et laissez la reposer; faites ensuite autant sur le travers, puis roulez la troi fois de le meme façon. On l’emploie de l’épaisseur d’une ligne á deux lignes.

Way of P. Marcelais

Take a well beaten butter pound and without water, crush it in a pound and half of flour, add there ice-cold water a bottle of wine, a salt pinch, if your butter is not too salty; roll that thin, made in a roller, piece the two extremities together, beat the paste, and let rest it; made then as much on through, then roll the third time in the same way. It is employed thickness of a line or two lines.

Façon de Mme. Tulloch

Une livre de farine dans un vaisseau avec une chopine d’eau glacée, délayez et étendez cela, de l’épaisseur d’un demi doigt; ayant prepare en palettes minces, trios quarterons de beurre pres

Way of Mrs. Tulloch

A pound of flour in a vessel with an ice-cold water bottle of wine, water and extend that, the thickness of a half finger; having prepares out of thin pallets, trios quarters of butter near

Pâte Brisée

Faites fonder une demi livre de beurre dancs un de miarre de lait, jettez cela chaud dans unelivre de farine, travaillez le tout pour l’employer á votre gout, de l’épaisseur d’un demi doigt; si l’on veut la rendre plus amollie, on y ajoute un peu de saindoux.

Pie crust pastry

Dissolve a half pound of butter in a milk de miarre(morning milk?), mix that hot in a pound of flour, work the whole to employ it to your taste, the thickness of a half finger; if one wants to return it more softened, one adds a little lard to it.

Pâte feuilletée

Quelques personnes font la pâte feuilletée, livre de beurre pour livre de farine, avec une chopine d’eau glacée, et la préparent au froid, ce qui la fait bien riche.

Puff pastry Some people make the puff pastry, one pound of butter for pound of flour, with an ice-cold water bottle of wine, and prepare it cold, which makes it quite rich.

My recipe for the pastry is a simply hot water pastry crust as shown below.

Tourtierre (Traditional Canadian Pork Pie)

This traditional Canadian minced meat pie with nutmeg seasoned ground pork, and shredded potato, onion and carrot filling is a dish I’ve been making for decades. There are many variations across Canada, this one is mine. Traditionally served on Christmas Eve, it is often seen gracing the table of many celebrations.

Servings: 6 dinner sized servings

2 pound(s) ground pork or 1 lb ground pork, 1 pound ground beef

1 large onion, minced

1 large russet potato, shredded

2 carrots, shredded

1/4 cup(s) flour, or 2 tablespoons cornstarch

1/2 cup(s) beef stock, or chicken stock

1 teaspoon(s) dried thyme

2 bay leaves

3 tablespoon(s) sage, crumbled

1.5 teaspoon(s) nutmeg, freshly grated

1 teaspoon(s) black pepper

1 teaspoon(s) sea salt

1 pie crust, double

1 egg, pasty wash

Directions:

Heat a large sauté pan. Add ground meat, cook until pink is gone, stirring to break up any chunks. add onions, bay, thyme, season with salt and pepper. Drain fat and reserve.

Combine cooked meat with remaining spices and herbs, shredded vegetables ,stock and flour. Remove bay leaves. Set aside.

Roll each piece of dough to ¼ inch thickness, enough to cover a 10″ pie plate with 2 inches over hang. Lay in a deep large pie pan. Brush the bottom of the pie dough with beaten egg. Fill with meat mixture.

Cover with pastry top. Fold pastry over and pinch closed. Trim excess pastry off pan and reserve for Potés recipe.

I use the pinch and forefinger method to finish the edge of the pie in this image. Brush with egg wash or milk. Cut 4 vents in a cross. Place a piece of cut dough for decoration and baste with egg again. Bake 350 degrees for 1.5 hrs or until baked through. You may need to cover the edges to prevent burning the crust before the pie is done. I typically will check the dough at the sides to get a sense of doneness.

I use the pinch and forefinger method to finish the edge of the pie in this image. Brush with egg wash or milk. Cut 4 vents in a cross. Place a piece of cut dough for decoration and baste with egg again. Bake 350 degrees for 1.5 hrs or until baked through. You may need to cover the edges to prevent burning the crust before the pie is done. I typically will check the dough at the sides to get a sense of doneness.

Let cool for 10-15 minutes and cut into 1/6’s or 1/8’s. Serve with your favorite salad. You can cover with foil and store in the freezer. and then thaw to serve later.

Potés; a special treat for the bakers.

My Mémé always saved the best for last. When we finished making the pork pie, or any pie for that matter, the bakers got a special treat using the leftover dough. It is simple enough that I don’t think a recipe necessary.

Using remaining dough, roll out into a circle, make a thin layer of your favorite compote, jam or jelly whatever you have on hand. Roll the dough up in a pinwheel. and slice. Place in a greased tin, brush with milk or beaten egg and sprinkle with granulated sugar. Also, I was taught to roll it out and fill the center, fold and seal, brush with milk or beaten egg then sprinkle with sugar. Bake alongside the tourtiere for about 25- 30 minutes. Remove from the oven, let cool enough to eat and enjoy with a hot cup of tea or coffee.

Pastry 1: Hot Water Pastry Recipe

Never Fail Recipe from Loretta Jennings

Ms. Jennings and I met while travelling by bus to Toronto, we both were flying out of Pierson Airport there to visit family in British Columbia. She was an 82 year old lady who had a heart as big as Canada. I think she was from Hamilton or the greater Toronto area (The Six) but I can’t remember now. We shared a lot in common. We talked about cooking (my favorite topic), she told me she had a pie business that kept her quite busy. I lamented about my poor excuse for pie crust. She then told me her “never fail” recipe and I was absolutely touched by her generosity of spirit and open mindedness. The recipe she said, had been in her family for at least 4 generations making in around 150 years old at the time. It turns out we had more than cooking in common as we shared our stories of adoption, mine of being an adopted child, hers of being a birth mother who gave up her little girl to a loving family. She told me how she never hid the fact from her family and that some time later her ‘little girl’ found her and they were able to share their lives again. What a wonderful lady. I am blessed to have met her. Funny that I was going to visit my father who I had found only 4 years before, and she was going to visit her son. The world works in circles.

This is the best pie crust I have ever made or tasted and the easiest to work with. It makes pie making a cinch. We tried the recipe when I got to B.C., and made two tortierre, an apple and a pumpkin pie (7-9” pie crusts in all).

1 lb lard

1 cup hot water

4 cups cake and pastry flour

1 cup all purpose flour

1 tsp salt

1tsp Baking powder

Pour boiling water over the lard and smooth out then stir until creamy. Add the flour salt and baking powder and combine well. It will be very wet, so just cover with plastic wrap.

Refrigerate 4 hours or overnight. Store in fridge 3 weeks and roll as needed (keep covered). Pliable at all times and never toughens. Freezes well.

Remove the needed amount and roll out to size of dough required (1.5″ beyond edge of pie pan) for bottom crust. ¾ “ for top. I typically roll my dough about 1/8″ thick

If cooking a frozen pie; Oven at 375 degrees for 45 minutes, don’t pre heat, don’t defrost pie (fruit pie 8”)

BON APPETIT!

References;

[i] – Scully, Terence, ed. Le Viandier de Taillevent. An Edition of all Extant Manuscripts. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1988.

Source http://www.godecookery.com/goderec/grec69.htm

[ii] Du fait de cuisine 1420, by Maistre Chiquart

translated by Elizabeth Cook

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Cookbooks/Du_Fait_de_Cuisine/Du_fait_de_Cuisine.html

[iii] Le Cusisinier Francais by Varenne, Pierre Francois translated into English in 1653 by I.D.G. With an introduction by Philip and Mary Hyman, Southover Press 2001

2 Cockshut Road, Lewes, East Sussex BN71JH ISBN 1 870962 17 6

[iv] La cuisinière canadienne, contenant tout ce qu’il est nécessaire de savoir dans un ménage, pour préparer les diverses…. Montréal: L. Perrault, 1840 Courtesy of Collections Canada, found at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/cuisine/002001-100.01-e.php, link active as of 10/20/2008